What is a conference? Common definitions provide only a vague sketch: “a meeting of two or more persons for discussing matters of common concern” (Merriam Webster a); “a usually formal interchange of views” (Merriam-Webster b); “a formal meeting for discussion” (Google a).

What qualifies as a meeting? Are all congregations of people in all places conferences? How formal must it be? Must the borders be agreed upon? Does it require a designated name? What counts as a discussion? How many discussions can fit in one conference? Does a sufficiently formal meeting held within the allotted times and assigned premises of a larger, longer conference constitute a sub-conference?

Absent context, the word verges on vacuous. And yet in professional contexts, e.g., among computer science academics, culture endows precise meaning. Google also offers a more colloquial definitions that cuts closer:

A formal meeting that typically takes place over a number of days and involves people with a shared interest, especially one held regularly by an association or organization. (Google)

However, this definition is also too amorphous, applying equally well to corporate conventions, trade shows, symposiums, and publishing conferences. It covers the International Conference on Machine Learning and also covers Comic Con.

A Cursory Word-sense Disambiguation

Even within the walls of academia, the term carries such disparate meanings that academics from different fields, when uttering “conference”, are mutually unintelligible. Among medical professionals, conferences are forums for networking and continuing education. In my adventures as a computer scientist living among economists and business faculty, I’ve found that, to my colleagues, conferences are forums disseminating research, networking, tutorializing, and recruiting. While papers are presented, these non-archival selections are lightly and permissively reviewed on the basis of extended abstracts. They are precisely what computer scientists call workshops.

In the broader computer technology industry, conference typically denotes events more specifically described as trade shows. The best-known among these (CES, Amazon re:Invent, Google I/O, O’Reilly Strata), sport enormous, broad, self-selecting audiences. No qualifications (besides registration fee) are assumed. They are professional gatherings for commerce and business development. While attendees and speakers preach the gospel of innovation and disruption, the center-stage innovations and disruptions are products and business models, not advancements at the frontiers of human knowledge. Academics may speak, but only to vulgarize.

In computer science, conferences share format and disposition with their counterparts in other academic fields. And they share subject matter with their industrial counterparts. However, in computer science, the assumed meaning of conference, has added significance. The primary function of the top conferences is to serve as the primary archival publication venues for the field. The greatest effort in preparing the conference consists of the peer review process that unfolds over months before the event (8+ for NeurIPS). The main conferences are virtually the only imprimatur that matters, and the greatest share of each conference concerns the presentation and recognition of works published that year. These venues exist to advance knowledge, and include professional development activities secondarily, as a means to this end.

Yawning discrepancies exist across the academic and technical professions on what precisely constitutes a conference. And occasionally, as when interdisciplinary computer scientists must explain their publishing output to non-CS faculty for whom the term conference paper rings alien at water coolers and annual reviews (hypothetically, of course), the conflicting nomenclature can be an annoyance.

But within the practice and organization of computer science conferences, we have seldom had to ask, what is a CS conference? What is its purpose? Who should come? What activities ought to take place there? These questions have always had unwavering answers and thus never required answering.

Who will come? The people that always come. Why are they coming? To present their latest work and to see others present their latest work. What activities should take place? Eating food, listening to talks, eating food, presenting posters, eating food… The details are always up to the organizers. Some conferences have better food. Some have better talks. But the very nature of the conference has seldom warranted contemplation.

Owing to the novelty of needing to ask such questions, the ML community has been caught by surprise by recent transformations. While we have continued to offer registration at large [see final section for more nuanced discussion], the constitution and purpose of conference goers has shifted. As the sponsorship booths have grown from the ad hoc folding tables of 2013 to massive installations in expo halls, we have simply rented bigger rooms and drawn beefier sponsorship fees. As conferences have sold out sooner and sooner, we have conceded that laggards, even among the core research community (barring exemptions for authors of accepted papers) will not attend. Unaccustomed to asking, within discipline, what a conference is, we suddenly find these conferences transformed, with no clear sense of who (if anyone) decided upon the change.

A Brief MyopIC History of NeurIPS

My initiation to NeurIPS came in 2013 as a first-year PhD student. While the conference was already rapidly growing, nearly everyone that I encountered was engaged in academic work in the field. The sponsor section consisted of less than 10 folding desks belonging to Amazon, Google, Microsoft Research, (possibly Facebook?), and Skytree (the internet suggests they still exist as a subsidiary of Infosys).

These companies appeared primarily concerned with recruiting research interns, although my view as a new researcher and potential intern recruit may have been skewed. In, perhaps, a sign of things to come, Mark Zuckerberg made an appearance at an onsite private event, inviting a mixture of gawking and incredulity.

Two years later, I attended NeurIPS 2015 in Montreal, and while the conference had grown considerably, the vast majority of attendees were still active researchers. Arguably, the growth still owed more to scale than to a fundamental transformation in the event’s character. As one symptom of the conference’s growth, half the audience had to watch the plenary talks (talks were still attended then) from the breakfast buffet room, which doubled as an overflow viewing area. As one early indication that not only scale but a shift in character was at play, the sponsor booths, long an afterthought, had grown into a full-fledged feature of the conference and unofficial invite-only sponsored parties came to dominate after-hours socialization.

With this change came free drinks and a surfeit of canapés for the invited, but also a credible threat to the role of the conference as a place of unmitigated exchange of ideas. Already, the parties artificially carved up the social structure. Absent a conscious plan to cut against the corporate party culture, who precisely you might see on any given evening depended first on who was invited to the same parties. That year I met a future research mentor during a gathering hosted by Microsoft Research Labs. Our conversation continued as we walked over to another hosted by DeepMind where it was abruptly cut short owing to only one of us being on the list. Over the successive 3 years, I have been party to tens of social plans shaped or aborted to some measure on account of the whims of the invite lists.

However, still, at that time, all academics that wanted to attend could at least register (funding permitting).

A ProtoTypical Trade Show

The following summer, David Kale, my collaborator in a string of papers applying modern recurrent nets to clinical (medical) time series data, roped me in to giving a talk at O’Reilly’s Strata+Hadoop World, a large conference of the industry trade show variety. While elder ML community members might have already begun to grumble that NeurIPS was becoming a spectacle, at Strata I found a veritable circus.

The audience spanned managers, developers, salesmen, solutions architects, marketers, investors. Most conversations consisted of buzzword soup. Most talks contained no more technical depth than a press release. And while NeurIPS’s sponsor room, with its abundant t-shirts and knickknacks seemed excessive, Strata occupied an entirely different stratum. By comparison, the NeurIPS sponsor booths seemed quaint. At Strata, the expo room was the beating heart of the conference. Company reps prowled for sales beneath towering foam-and-plastic edifices. Neon lights, bespoke cubbies, and high-res displays defined the norm. T-shirt cannons, mascots, and cheerleaders would not have been out place.

The greatest Trade Show North of Vegas

Just two years later, in the run-up to NeurIPS 2017 (Long Beach, California), researchers expressed shock to discover that registrations (increasingly called “tickets”) sold out even before decisions for workshop papers had been announced (submissions and decisions for workshop papers typically trail the archival proceedings by 2-3 months). While extra slots were eventually allotted to (some) authors of accepted workshop papers, not every author of every paper could attend.

Perhaps for the first time, authors of research papers (non-first authors of workshop papers) were denied entrance to the conference while priority had been given to a large cohort of non-academics—recruiters, managers, investors, developers, and reporters—simply because they were quicker on the trigger.

Inspired by this absurdity, I posted a satirical piece shortly after, announcing that ICML had sold out even before the call for papers was announced. Despite filing the tortured caricature under a dedicated Satire category, many readers, acclimated to a field drifting off the rails, took it seriously. The article was picked up and circulated as news by a number of AI newsletters, (including an official NYU data science newsletter). Some ICML organizers earnestly asked me to retract the post, concerned that despite the clear markings of satire, it was nevertheless distressing potential attendees. They did not share my view that this ought to be the essential purpose of satire, to push readers to realize how far reality had drifted into the absurd.

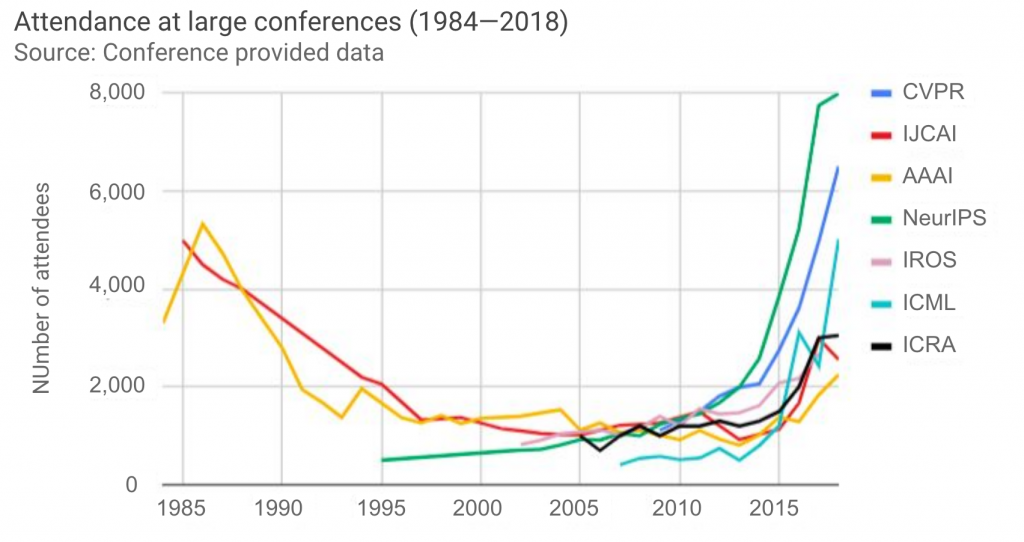

This year, from December 3rd to 8th, 8000 researchers registrants descended upon Montreal’s Palais de Congrès to participate in NeurIPS 2018. Again, the attendance count was right-censored due to the excess demand for a fixed supply at this year’s prices ($750 for general registrants, $425 for students).

The supply-demand imbalance was so severe that the conference sold out in 12 minutes, inviting mocking comparisons to Burning Man, the counterculture experiment-cum-SV libertarian & banker-bro retreat that sells out each year in similarly spectacular fashion, focuses on similarly over-the-top exhibitions and parties, and caters to a (increasingly similarly) self-selected audience.

Perhaps, for the first time, most researchers that did not have (any) authored conference papers, (first-) authored workshop papers, or senior status in the community could not attend. A number of junior authors cobbled together workshop submissions, not for academic interest but to garner a lottery ticket that might, with 40-50% probability, materialize as a registration slot. And yet, with many researchers on the sidelines, many of the 25% of seats released at large were scooped up by spectators. This year, for the first time, I recognized fewer researchers in the halls than in the prior year. This may have owed both to researchers denied admission, researchers opting to sit this one out, and to the larger total number of attendees. Many invited talks, while reasonably engaging, were so general as to be palatable at TED. In my opinion, the character of the conference drifted discernibly away from research.

While NeurIPS made great strides towards inclusivity in traditionally overlooked dimensions—Women in Machine Learning and Black in AI continued to be highlights of the conference—it cratered in dimensions that traditionally no one needed to worry about. The conference struggled to ensure the inclusion of the research community itself. With capped capacity and registrations at large, registration became a zero sum game.

The Objective Function

The breathless coverage, both by the press and in-community bodies, like the Artificial Intelligence Index 2018 Annual Report, charts the development of the community via aggregates like the number of attendees, number of papers submitted, amount of money spent, etc. These signs of progress are fine statistics to know, but by themselves are meaningless. Lost in these coarse proxies for growth and progress is any semantic anchoring to what precisely the conferences, the papers, or the community are actually doing. Lost is the semantic grounding to decipher what if anything, any of it has to do with research.

We should look to internet-era journalism as a cautionary tale. As consumers moved to an a la carte consumption model, and suddenly it became possible to track and obsess over quantitative measures of success (clicks, impressions, subscribers), the very character of the journalistic outlets morphed rapidly. Lost in this myopic optimization is any consideration of what if anything the underlying work has to do with journalism. The key metrics that track success in online content creation fail to distinguish between journalism and pornography, just as our measures of community growth and success fail to distinguish between machine learning and industry trade shows.

The sudden, passive transformation of our research summits into trade shows should alarm all members of the field and warrants immediate action to fortify the character of the event as a summit first and foremost for bringing together the research community. Not a single motivated PhD student should be denied entry while spectators attend. Even among those who could attend, the shifting character of the event has led a growing cadre of researchers to sit out the conference, opting instead to allocate their travel days to smaller, more academic gatherings.

We ought to form a task force at the highest level to track the shifting character of the event, and to provide a reward signal wherein 2nd, 3rd, 4th authors being shut out of a conference that features their own work while thousands of non-academics score tickets constitutes a failing grade.

Corrective MeasureS

There is a limited time to act to bolster the academic function of NeurIPS and ICML as places for the dissemination of research and the de facto meeting places for members of the research community before they irreversibly transform into industry trade-shows where obligatory poster sessions are no more than a vestigial reminder of the meetup’s roots. To kick-start a constructive conversation about what can be done, here are a few recommended actions:

- TWO-MONTH ACADEMIC-ONLY REGISTRATION PERIOD:

For 2 months after opening registrations, allow only academics to register. Here, academics might loosely be defined as current students and faculty, and authors of current and past papers. This period should run through the end of workshop decisions. - DECIDE IF (OR WHICH PARTS OF) NEURIPS IS (ARE) PUBLIC:

This year’s the conference mishandled the press—they were shut out of workshops under the pretense that NeurIPS was an event held under Chatham house rules [it is not]. This owed to a failure to recognize that the conference had already become a public event. In short, each section of the conference must either be clearly public or clearly academic. Sections open to the general public must also be open to journalists. And if we are not ok with journalists attending, then why are we ok with corporate comms personnel attending those same workshops? - CURTAIL THE EXPO EXTRAVAGANZA:

The expo hall takes too much attention away from the academic events. The room is full of free knickknacks, free food, posh seating, and millions of dollars pumped into flashy attractions. Scientific talks and posters should not have to compete with a CES-style expo hall for attention. A potential compromise here could be to shut down the expo room during certain days or at certain times. By comparison the balance at EMNLP this year was far healthier. People mingled around the Expo rooms during breaks but they were deserted (including by company reps) during most talks. - REFORM SPONSOR EVENTS TO BE OPEN TO ALL RESEARCHERS:

The desire of companies to recruit is perfectly rational. And there’s not much the conference can do to enforce what companies do off-premises and after hours. However, it may be possible to require sponsors to enter into a compact that shifted extracurricular activities (perhaps pooling efforts together) that did not exclude any researchers. The current party culture brings together the socially-connected (regardless of discipline), the recruitable (hot PhD candidates and junior researchers) and established well-known researchers. But excluded are those young researchers who would most benefit most from the opportunity to get to meet potential employers, advisors, and mentors.

Updates Per Feedback from Organizers

One important item to stress here: this is a general problem that none of us are prepared for. It’s also a problem that stems from the very interest in our field that nearly all of us benefit from via job security, industry employment, research funds, etc. Moreover, the organizers did not ask for this problem and have likely done as well or better than any among us might in their shoes struggling to cope with the same growth. Shortly after posting this piece, I received a constructive email from Samy Bengio, this year’s general chair that was remarkably level and while he expressed agreement with some concerns, he also reasonably pointed out some points that my original post overlooked:

- To some degree, the zero-sum aspect of registration owes to the conference’s size. The Vancouver venue slated for the next two years can accommodate 14,500 attendees. On the other hand, as Yisong Yue reminded me, SIGGRAPH topped out at roughly 45,000 attendees. It seems likely that we might exceed Vancouver’s capacity within two years. We ought to decide both (i) what to do when that happens and (ii) whether we indeed want the conference to swell to whatever size the public demands. In a 45,000 person conference, we will no longer bump into real researchers serendipitously. Young researchers without social connections might never meet professors at a conference that size.

- Samy also rightly pointed out that the initial at-large registrations covered only 25% of slots. The remaining 75% were indeed reserved for members of “the community”. Among these were (quoted from correspondence):

- All authors of all accepted papers at the conferences

- One third of the reviewers (the best ones, as selected by area chairs, we’re talking about more than a thousand of them)

- All area chairs and “above” (senior area chairs, program chairs, organizers, etc)

- Hundreds of registrations kept for Black in AI, LatinX, Queer in AI and WiML- [and] hundreds of additional registrations kept for authors of accepted papers at workshops.

While many of us may advocate for stronger measures to protect the academic character of the conference, it’s also important to acknowledge that the organizing committee put in considerable thought to dealing with a situation that few among us would have been prepared to handle.

“A number of junior authors cobbled together workshop submissions, not for academic interest but to garner a lottery ticket …”

Shirley, you jest. Can you list examples?

I should more accurately have said “not purely out of academic interest, but also to garner a lottery ticket”. That is to say, many people submitted papers that they otherwise might not have / submitted multiple rushed papers to multiple workshops, motivated in part by the prospects of admission to attend the conference.

Examples of multiple, rushed papers? Without naming names, of course.

1) There is not way to give such an example without effectively naming a name so I’ll abstain.

2) It’s ok for a workshop paper to be a bit rushed. After all, workshops explicitly call for late-breaking results and works-in-progress. More problematic though is a) the motivation b) that it’s made necessary by the registration situation.